On a summer afternoon, it’s easy to spot the hottest parts of town on a heat map, and schools and playgrounds often glow bright red. During our heat mapping campaign, we found that air temperatures and WBGT values near several schools were noticeably higher than in nearby (mostly shaded) areas. This isn’t unique to our area; schoolyards and playgrounds in general tend to heat up faster and stay hotter because of limited shade and an abundance of heat-retaining surfaces like asphalt, rubber, and metal. Understanding why these spaces become hot spots can help communities make them safer and more comfortable for some of our most vulnerable age groups and populations.

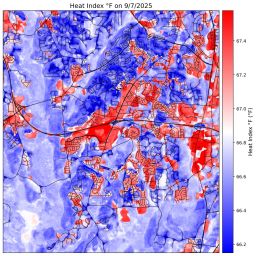

On July 29th, we took advantage of a break in our official heat mapping schedule to explore some of these hot spots around local schools. It was a fairly typical mid-summer day, with afternoon temperatures at the Raleigh-Durham Airport (RDU) running between 93 and 95°F. Around the school grounds, however, our HOBO sensors told a different story. Air temperatures ranged from 98 to 103°F, about 5 to 8°F hotter than those at RDU. In terms of the heat index, RDU topped out around 99°F, while some of our school measurements climbed to near 110°F, meaning the schools weren’t just hotter, they were also more humid.

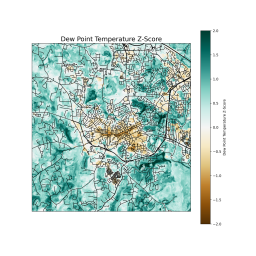

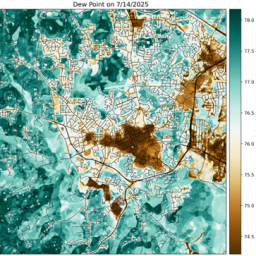

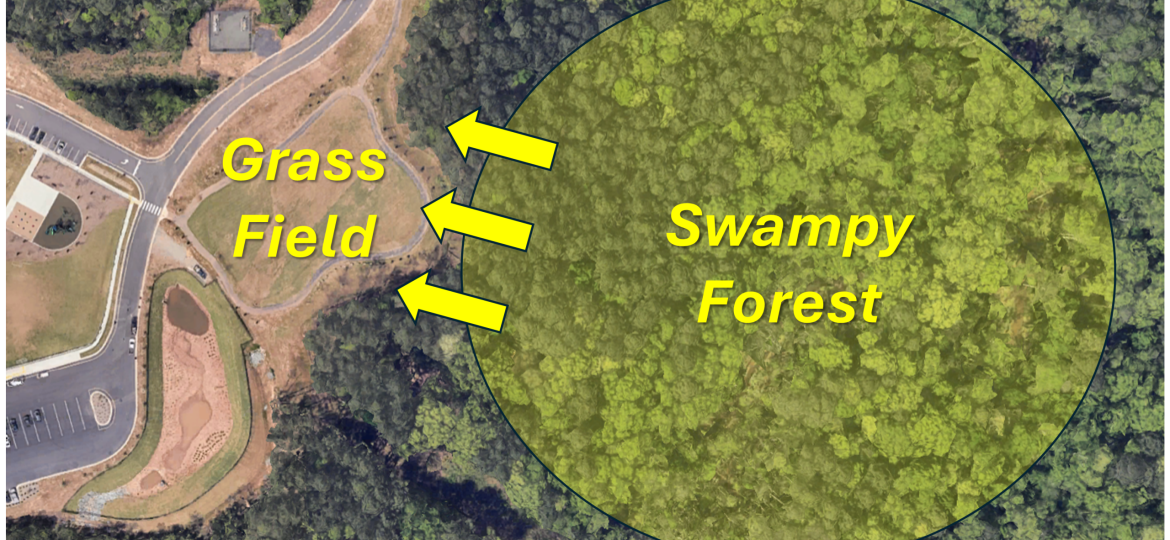

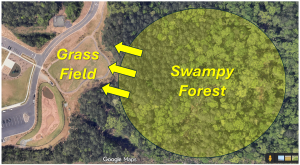

One of the more interesting observations on this day came from a grassy field next to a swampy forest on the east side of one of the schools (see figure below). Winds were light (less than 10 mph) and out of the east, carrying extra moisture from the forest across the field. As a result, dew point temperatures there rose to 72°F, the highest we recorded anywhere during this experiment (by comparison, dew point temperatures at RDU that afternoon were around 65°F). That moisture likely came from the lush vegetation and wet soils resulting from a very humid and rainy summer. From April to July, a nearby CoCoRaHS rain gauge recorded over 21 inches of rain, about 30% more than normal, which meant plenty of water was available for evaporation and transpiration.

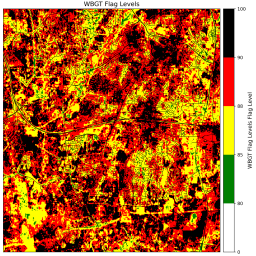

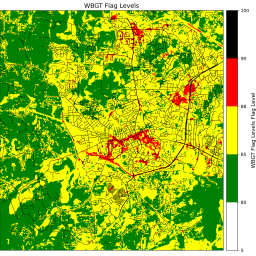

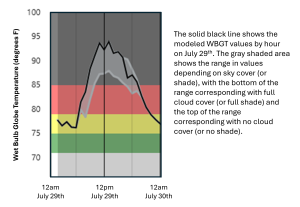

While we didn’t produce a WBGT heat map for this day, our WBGT Prediction Tool showed values near the school peaking around 94°F during the midday hours, conditions that would trigger a black flag warning under any established WBGT guidelines, including those used by the American Academy of Pediatrics (see figure below). This means outdoor activities, especially for young children, should be canceled. Even by the time we started collecting data around 2:15pm, modeled WBGT values were still in the upper 80s. That’s dangerously high for children, and it underscores an important point: regional conditions tell only part of the story. Local conditions and environments, like the mix of sun, shade, pavement, and moisture around a school, can amplify heat stress far beyond what’s measured at the nearest airport or weather station. And if that weren’t enough, playground surfaces like asphalt and rubber can easily become hot enough to cause burns in seconds, especially in direct sunlight.

As our findings show, schoolyards and playgrounds can quickly become some of the hottest places during summer afternoons. But the solutions don’t have to be complicated. There are a number of things that can be done to reduce heat exposure and make outdoor spaces safer for kids, teachers, and families. The single most effective way to reduce heat on school grounds is to increase shade. Trees and shade structures can lower surface temperatures by over 40°F and create much more comfortable microclimates (see figure below). Full-area shade that covers the majority of playgrounds and seating areas can dramatically reduce the risk of heat stress and burns. As such, cities and school systems should treat shade as a basic necessity, just like sidewalks, water fountains, and crosswalks. Shade coverage requirements can be built into local design standards and zoning codes to ensure that future schools and playgrounds are planned with heat safety in mind from the start.

As our findings show, schoolyards and playgrounds can quickly become some of the hottest places during summer afternoons. But the solutions don’t have to be complicated. There are a number of things that can be done to reduce heat exposure and make outdoor spaces safer for kids, teachers, and families. The single most effective way to reduce heat on school grounds is to increase shade. Trees and shade structures can lower surface temperatures by over 40°F and create much more comfortable microclimates (see figure below). Full-area shade that covers the majority of playgrounds and seating areas can dramatically reduce the risk of heat stress and burns. As such, cities and school systems should treat shade as a basic necessity, just like sidewalks, water fountains, and crosswalks. Shade coverage requirements can be built into local design standards and zoning codes to ensure that future schools and playgrounds are planned with heat safety in mind from the start.

Obviously, shade is important, but surface materials matter, too. Dark rubber, asphalt, and synthetic turf can reach dangerously high temperatures in direct sunlight, sometimes exceeding 180°F! By contrast, natural grass, certain engineered play surfaces, and lighter-colored pavements stay much cooler. When schools plan new playgrounds or renovations, choosing materials that absorb less heat can make a major difference. Along with shade structures, cool surfaces should be treated as essential infrastructure.

In addition to modifying the physical environment, schools can also strengthen heat awareness through formal heat mitigation plans that include staff training, hydration and rest policies, as well as access to heat-awareness tools such as temperature or WBGT alerts or educational materials for students. Establishing appropriate thresholds to guide activity levels, similar to athletic programs, can help prevent overexertion and protect children during high-heat days. A great example of this is the HeatReady Schools project, which was developed in the Phoenix area but provides an excellent model with resources for schools in other parts of the country.

Ultimately, reducing heat risk is a shared responsibility among schools, parents/caregivers, planners, and the broader community. By recognizing heat as a real and preventable hazard, we can make sure schoolyards are places for safe play, learning, and connection.